As humans, we instinctively fear the unknown, often turning abstract fears into tangible symbols to regain control. Monsters are among the most enduring symbols humans have conceived to embody fears and unknowns. As Jeffrey Jerome Cohen explains in Monster Theory, ‘The monster is continually linked to forbidden practices, in order to normalize and to enforce. The monster also attracts’.[1] This duality is evident in how medieval art and literature depicted monstrous races at the margins of the world, blending fear with fascination. Across cultures and centuries, monsters have been depicted as both literal and metaphorical entities, evolving to reflect the unique anxieties, beliefs, and power dynamics of their times. But also used to explain natural phenomena, enforce social hierarchies, and inspire both awe and terror. But monsters were also tools for defining identity: a way of separating ‘us’ from ‘them.’

The late Middle Ages witnessed a rich tradition of ‘othering’ through monstrous imagery. Maps, manuscripts, and artistic representations abounded with figures that blurred the line between human and non-human, familiar and alien. These constructions served not merely as imaginative entertainment but as semiotic markers of cultural, religious, and political boundaries. For example, medieval art frequently linked physical appearance with moral character, drawing on ancient theories about the influence of climate and geography on human nature.[2] Such views reinforced the dichotomy between the civilised centre and the barbaric periphery, with physical distortions used to symbolise spiritual deviance. Maps, such as the Hereford Mappa Mundi, illustrated these boundaries visually, placing monstrous races like the Blemmyae and Sciapods at the edges of the known world. Such depictions were not just artistic; they reinforced ideological hierarchies, as described by Garcia, who notes that maps ‘hide a political discourse and a cultural reading of the world’.[3] The monstrous body became a site for projecting otherness, embodying the cultural taboos, latent desires, and fears of a society.[4] In this essay, we explore how the exotic and the threatening, as embodied by monsters and ‘others’, defined the worldview of late medieval Europe.

The Monstrous as a Mirror of the Other

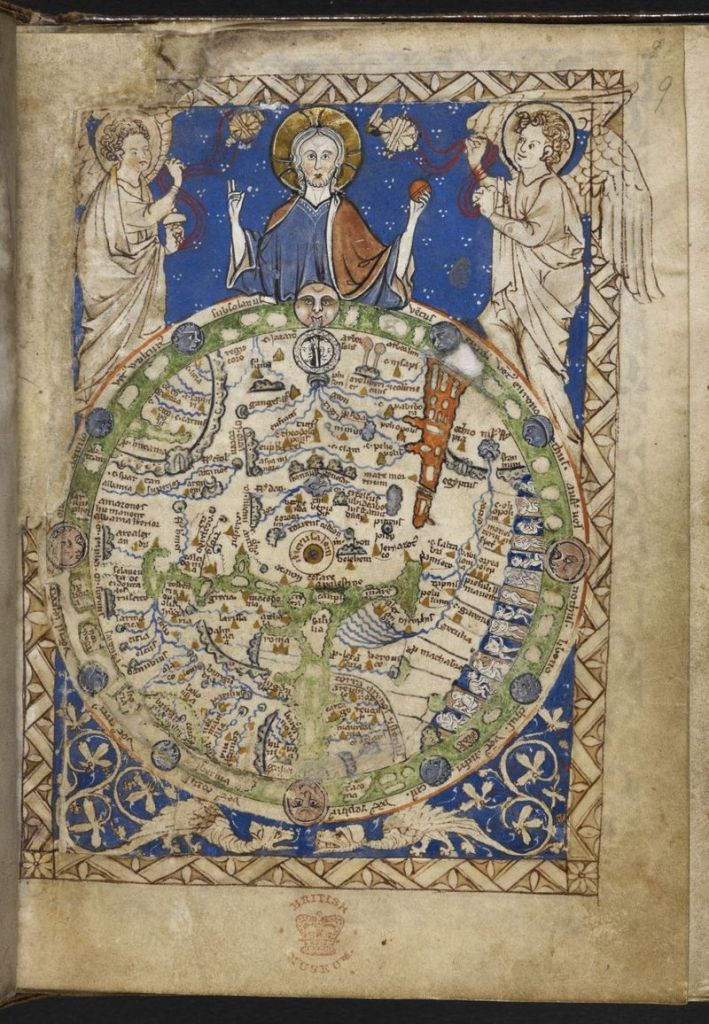

Rosi Braidotti argues that monstrosity is an omnipresent construct, one that reflects cultural alterity: be it ethnic, sexual, or political.[5] In the medieval period, this ‘otherness’ was often depicted on the fringes of known geography. Mappae mundi, large scale world maps such as the Hereford Map, were not merely geographic tools but cosmological diagrams. These maps situated Europe as the centre of civilisation, while the periphery teemed with monstrous races: cynocephali (dog-headed men), sciapods (single-legged people), and anthropophagi (cannibals).[6] These creatures were visual metaphors for the unknown and ungovernable, embodying the limits of the medieval Christian worldview. The ‘monstrous’ on maps like these became a spatial and symbolic representation of the unfamiliar and the dangerous.

St. Maurice, c.1240-50, Magdeburg Cathedral.

The conceptual blending of monstrosity and otherness extended beyond maps. Monstrous races were used as metaphors for unknown dangers and as justification for conquest or exclusion. Medieval art and literature employed a ‘pictorial code of rejection’ to represent the exotic other. As Debra Higgs Strickland notes, this visual language was flexible, adapting to different cultural and political contexts. Muslims, Jews, and other non-Christians were depicted with exaggerated physical traits that symbolised their supposed moral and spiritual corruption.[7] These images were not merely descriptive but prescriptive, shaping how medieval Europeans viewed and interacted with these groups.

Distinct from the imagery of monstrous races, depictions of ethnicity in the Middle Ages often carried theological implications. Robert Bartlett identifies three ways ethnicity was handled in medieval illustrated texts: through textual cues that do not depict visual differences, through physiological differentiation such as exaggerated features like the ‘Jewish nose’ or depictions of black Africans, and through imagined races drawn from ancient sources like Pliny’s Natural History.[8] These depictions frequently reflected theological concerns rather than purely societal ones. For instance, St. Maurice, a black saint heroically depicted in Magdeburg Cathedral around 1240-50, emphasised Christian egalitarianism rather than racial division. Similarly, Hans Memling’s Last Judgement included both a black man among the saved and another among the damned, symbolising divine impartiality.[9] These portrayals highlighted the universality of salvation in Christian doctrine, contrasting with the physical distortions used to marginalise Jewish and Muslim figures, often emphasising their supposed spiritual deviance.

Hans Memling, The Last Judgement, 1467-1473. The National Museum, Gdansk.

The portrayal of monstrosity, however, went beyond theological or ethnic depictions. The Livre des Merveilles (Book of Marvels), a 15th century manuscript associated with the court of King René of Anjou, features an image of Ethiopia populated with Monstrous Races, a Wild Man, and fantastic birds and beasts. The barren desert landscape, with its caves and strange rock formations, was deliberately chosen to emphasise remoteness and wildness, as these settings carried negative connotations in medieval art and literature. Strickland notes that such locations were seen as “wild and remote places inhabited only by correspondingly wild and savage creatures”.[10] This connection between geography and monstrosity reinforced the idea that moral and physical otherness were tied to the extremes of the natural world.

Ethiopia as described by Marco Polo, Le Livre des Merveilles du Monde, c.1460. Piermont Morgan Library, New York, MS M. 461, fol. 26v.

For instance, Prester John, initially depicted as a white Christian ruler, became associated with Ethiopia and was later shown with dark skin on the Estense world map (1450-60). This shift reflected both geographic relocation and changing perceptions of his kingdom’s identity, illustrating the fluidity of monstrous and exotic imagery in medieval cartography.[11] Early medieval discourse often debated the spiritual status of ‘wondrous peoples’ in the context of divine creation. Did they have souls? Were they redeemable? As Silke Büttner observes, the ‘monstrous’ initially entered theological and natural histories as curiosities rather than outright dangers, reflecting an intellectual engagement with diversity rather than rejection.[12]

Prestor John. Estense Mappa Mundi, c. 1450-60. Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena (detail).

Monstrification in the Middle Ages

By the late Middle Ages, however, monstrosity took on a sharper edge, becoming a tool for political othering. The expansion of the Ottoman Empire, for instance, was met with a wave of anti-Muslim propaganda that depicted Turks as monstrous invaders. As Strickland highlights, enemies of the medieval Church were often portrayed as both spiritually and physically deformed, their ugliness serving as a visual marker of their moral failings.[13] Depictions of Muslims frequently used dark skin as a negative attribute, aligning them with other groups, such as Jews, to emphasize their exclusion from Christian norms. This included vivid illustrations and texts portraying them as subhuman. For example, the famous dog-headed cynocephalus figure was frequently used to represent Muslims, as Malouf describes, ‘combining the impossible and the forbidden’ to dehumanize their identity and underscore their perceived otherness.[14] The printing press amplified such imagery, producing countless broadsheets and texts portraying the Ottomans as subhuman foes of Christendom.[15] These representations fused physical deformity with moral deviance, reinforcing the notion of cultural and religious superiority.

Colour, clothing, and physiognomy were critical markers of difference. Turbans, for instance, became shorthand for non-Christian identity, while dark skin was associated with sin and otherness. Even seemingly neutral traits, such as beards, were imbued with negative connotations, symbolising deceit or barbarity.[16] These visual codes reinforced the dichotomy between ‘civilised’ Europe and the ‘barbaric’ periphery.

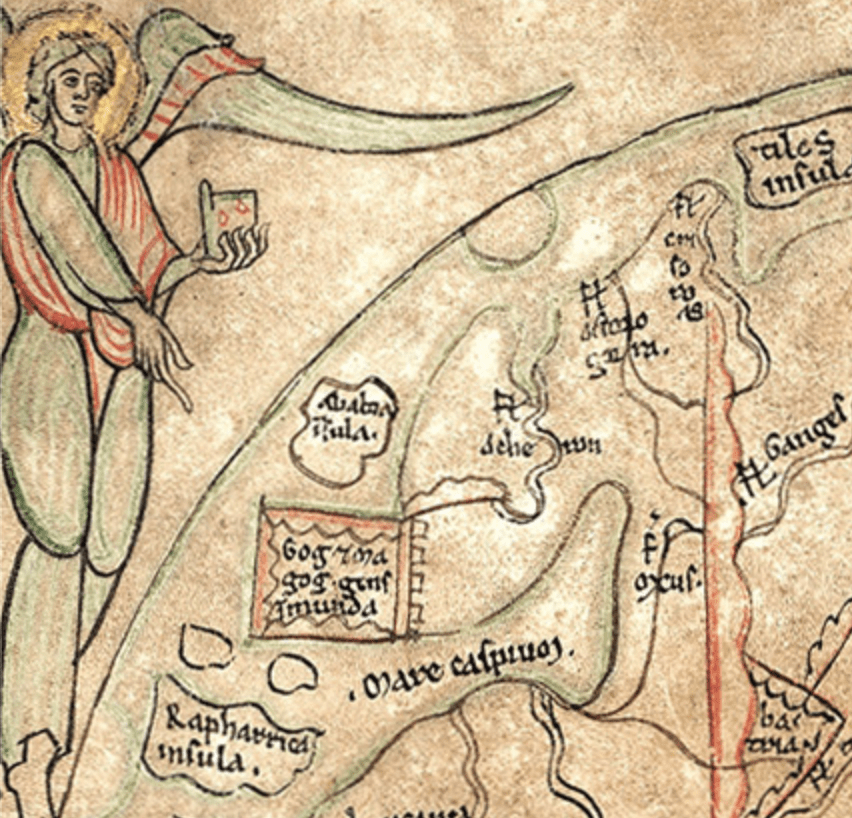

This process of ‘monstrification’ extended to other groups as well. Figures such as Gog and Magog, mythical allies of the Antichrist, symbolised the outer limits of civilization and the threats lurking beyond. [17] These figures were not just decorative but deeply symbolic, embodying apocalyptic fears and the perceived moral corruption of non-Christian lands. Ricold of Monte Croce, a 13th century missionary, claimed that the Tartars identified themselves as descendants of Gog and Magog, even deriving their name ‘Mongoli’ from ‘Magogoli’.[18] These figures, appearing on maps and in texts, were emblematic of the eschatological fears of Christendom, with Gog and Magog often associated with cannibals and unclean descendants of Cain who would break forth in apocalyptic times to war against Christians.[19] Geraldine Heng describes how Jews, Saracens, and Mongols were frequently equated with monstrous races in medieval cartography and literature. The blood libel, for example, painted Jews as blood-drinking, devilish figures—a stereotype perpetuated in texts and visual art to justify exclusion and violence.[20] On maps, these fears were spatially marked. For example, Johannes de Hese’s fantastical account places Gog and Magog imprisoned between mountains in a remote Asian region, embodying the vague and shifting conception of ethnic and apocalyptic threats in medieval Europe.[21]

Gog and Magog on the Sawley map (‚Henry of Mainz‘ map), c. 1180-1200. Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (detail).

This conceptual blending of monstrosity and otherness extended beyond maps. Monstrous races were used as metaphors for unknown dangers and as justification for conquest or exclusion. Medieval art and literature employed a ‘pictorial code of rejection’ to represent the exotic other. As Debra Higgs Strickland notes, this visual language was flexible, adapting to different cultural and political contexts. Muslims, Jews, and other non-Christians were depicted with exaggerated physical traits that symbolised their supposed moral and spiritual corruption.[22] These images were not merely descriptive but prescriptive, shaping how medieval Europeans viewed and interacted with these groups.

Colour, clothing, and physiognomy were critical markers of difference. Turbans, for instance, became shorthand for non-Christian identity, while dark skin was associated with sin and otherness. Even seemingly neutral traits, such as beards, were imbued with negative connotations, symbolising deceit or barbarity.[23] These visual codes reinforced the dichotomy between ‘civilised’ Europe and the ‘barbaric’ periphery.

Maps were a particularly potent medium for constructing otherness. The Hereford Mappa Mundi, for instance, displays monstrous races like the Blemmyae and Sciapods at the edges of the known world. Such figures embodied cultural and geographical marginality, echoing Strickland’s observation that ‘the geographical remoteness of the Races was conveyed most effectively on medieval mappae mundi’.[24] A striking example is the 13th century English Psalter map, where an assortment of monsters occupies southern Africa, underscoring their placement in regions associated with extreme climates. Alfred Hiatt explains that such maps, while ostensibly geographic, were ‘neither pure fantasy nor empiricism but a distillation of verbal descriptions into visual form’.[25] This cartographic tradition fused geography with ethnography, using monsters as proxies for racial and cultural differences. The monstrous races tradition provided the ideological infrastructure for imagining global diversity through a Eurocentric lens.[26]

The symbolic power of these maps lies in their ability to make the abstract concrete. By placing monstrous races in specific locations, mappae mundi reinforced the notion of a civilised centre and a chaotic, dangerous periphery. This spatial logic extended to real-world politics, justifying crusades, colonial ventures, and other acts of aggression against non-European peoples.

Mappa Mundi. Psaltar, c. 1265. British Library London, Add. MS 28681, fol. 9.

Conclusion

The late Middle Ages were a time of profound cultural and political transformation, marked by increasing contact with the ‘other’ through trade, travel, and conflict. Monsters and other exotic figures served as tools for navigating these encounters, embodying both fear and fascination. They helped medieval Europeans define their identity by contrasting it with the unknown and the alien.

Yet these representations were far from innocent. Whether through maps, manuscripts, or artistic depictions, the process of othering reinforced hierarchies of power and exclusion. By constructing the exotic and the threatening, medieval society mapped not only the physical world but also the boundaries of its own imagination. In doing so, it left a legacy of othering that continues to resonate in modern thought.

Further reading

Bartlett, Robert. «Illustrating Ethnicity in the Middle Ages.» In The Origins of Racism in the West, edited by Miriam Eliav-Feldon, Benjamin Isaac, and Joseph Ziegler, 132–156. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Braidotti, Rosi. «Teratologies.» In Deleuze and Feminist Theory, edited by Ian Buchanan and Claire Colebrook, 156–172. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000.

Büttner, Silke. «Eugen_ia. Oder: Im Netz der Ähnlichkeiten: Über Formen des visuellen Othering im 12. Jahrhundert.» In FKW: Zeitschrift für Geschlechterforschung und visuelle Kultur, no. 54 (2013): 11–27.

Camille, Michael. Image of the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art. London: Reaktion Books, 1992.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. «Monster Culture.» In Monster Theory, edited by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, 3–25. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. Of Giants: Sex, Monsters, and the Middle Ages. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

De Miramon, Charles. «Noble Dogs, Noble Blood: The Invention of the Concept of Race in the Late Middle Ages.» In The Origins of Racism in the West, edited by Miriam Eliav-Feldon, Benjamin Isaac, and Joseph Ziegler, 200–216. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Duby, Georges. Wirklichkeit und höfischer Traum: Zur Kultur des Mittelalters. Berlin: K. Wagenbach, 1986.

Edson, Evelyn. Mapping Time and Space: How Medieval Mapmakers Viewed Their World. London: The British Library, 1997.

Edson, Evelyn. “Petrarch’s Journey between Two Maps”. In: The Art, Science and Technology of Medieval Travel, edited by Robert Bork and Andrea Kann, 157-165. New York: Repr. Abingdon, 2016.

García, Pedro Martínez. „Mapping the ‘New World’: Medieval Traditions of Othering.“ In Vegueta: Anuario de la Facultad de Geografía e Historia, no. 18 (2018): 119–131.

Heng, Geraldine. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Hiatt, Alfred. «Maps and Margins: Other Lands, Other Peoples.» In The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Literature in English, edited by Greg Walker and Elaine Treharne, 649–676. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Kupfer, Marcia. “Traveling the Mappa Mundi: Readerly Transport from Cassiodorus to Petrarch.” In Maps and Travel in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period: Knowledge, Imagination, and Visual Culture, edited by Ingrid Baumgärtner, Nirit Ben-Aryeh Debby and Katrin Kogman-Appel, 17-36. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019.

Lavezzo, Kathy. «Complex Identities: Selves and Others.» In The Oxford Handbook of Medieval English Literature, edited by Elaine Treharne and Greg Walker, 434–457. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Malouf, Iyad. «Medieval Othering: Western Monsters and Eastern Maskhs.» In dibur literary journal 12–13 (2022): 25–35.

Mandeville, John. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, London: Penguin Classics, 2005.

Meier, Jan Niklas. «Das Monströse als Instrument einer Othering-Strategie in antiosmanischer Propaganda des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts.» In Mittelalter: Interdisziplinäre Forschung und Rezeptionsgeschichte, July 19, 2017. https://mittelalter.hypotheses.org/10776. Accessed December 2, 2024.

Strickland, Debra Higgs. Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Strickland, Debra Higgs. “The Bestiary on the Hereford World Map (c. 1300).” In Maps and Travel in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period: Knowledge, Imagination, and Visual Culture, edited by Ingrid Baumgärtner, Nirit Ben-Aryeh Debby and Katrin Kogman-Appel, 37-73. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019.

Vassilieva-Codognet, Olga. «Ambiguous Figures of Otherness: Redoubtable Beasts in Princely Badges of the Late Middle Ages.» In Animals and Otherness in the Middle Ages, edited by Francisco de Asis Garcia Garcia, Monica Ann Walker Vadillo, and Maria Victoria Chico Picaza, 133–150. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2013.

Westrem, Scott. «Against Gog and Magog.» In Text and Territory: Geographical Imagination in the European Middle Ages, edited by Sylvia Tomasch and Sealy Gilles, 54–78. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Young, Helen. «Whiteness and Time: The Once, Present, and Future Race.» In Medievalism on the Margins, edited by Karl Fulgeso, Vincent Ferre, and Alicia C. Montoya, 39–49. Studies in Medievalism XXIV. Rochester, NY: Boydell and Brewer, 2015.

[1] Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, ‘Monster Culture,’ in Monster Theory, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 3–25, 16.

[2] Debra Higgs Strickland, Saracens, demons, & Jews: making monsters in medieval art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 30.

[3] Pedro Martinez Garcia, ‘Mapping the ‘New World’: Medieval Traditions of Othering’, in: Vegueta. Anuario de la Facultad de Geografia e Historia, No. 18 (2018): 120.

[4] Jan Niklas Meier, «Das Monströse als Instrument einer Othering-Strategie in anti-osmanischer Propaganda des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts», in: Mittelalter. Inter-disziplinäre Forschung und Rezeptionsgeschichte, 19.7.2017, URL: https://mittelalter.hypotheses.org/10776 (02.12.2024).

[5] Rosi Braidotti, „Teratologies,“ in Deleuze and Feminist Theory, ed. Ian Buchanan and Claire Colebrook (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000), 156–172.

[6] Geraldine Heng, The invention of race in the European Middle Ages (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2018), 33-35.

[7] Strickland (2003), 241.

[8] Bartlett (2009), 132-133.

[9] Ibid., 136-137.

[10] Strickland (2003), 44.

[11] Ibid., 249.

[12] Silke Büttner, ‘Eugen_ia. Oder: Im Netz der Ähnlichkeiten: Über Formen des visuellen Othering im 12. Jahrhundert’, in: FKW: Zeitschrift für Geschlechterforschung und visuelle Kultur Nr. 54 (2013): pp. 11–27, 13.

[13] Strickland (2003), 29.

[14] Iyad Malouf, ‘Medieval Othering: Western Monsters and Eastern Maskhs,’ dibur literary journal 12–13 (2022): 25–35, 28.

[15] Jan Niklas Meier, «Das Monströse als Instrument einer Othering-Strategie in anti-osmanischer Propaganda des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts», in: Mittelalter. Inter-disziplinäre Forschung und Rezeptionsgeschichte, 19.7.2017, URL: https://mittelalter.hypotheses.org/10776 (02.12.2024).

[16] Büttner (2013), 13-14.

[17] Scott Westrem, ‘Against Gog and Magog,’ in Text and Territory: Geographical Imagination in the European Middle Ages, ed. Sylvia Tomasch and Sealy Gilles (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), pp. 54–78, 54.

[18] Strickland (2003), 29.

[19] Heng (2018), 35.

[20] Ibid., 15-16.

[21] Westrem (2016), 55-56.

[22] Strickland (2003), 241.

[23] Büttner (2013), 13-14.

[24] Strickland (2003), 41.

[25]Alfred Hiatt, ‘Maps and Margins: Other Lands, Other Peoples’, in: The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Literature in English, edited by Greg Walker and Elaine Treharne (Oxford: Oxford Academic, 2012): pp. 649-676, 654.

[26] Heng (2018), 35.