Medieval Europe had a special kind of genius for imagining that the world beyond its borders was full of strange creatures that no one in their right mind would want to meet on a dark night. If you couldn’t see it with your own eyes, the logic went, it was probably teeming with things that wanted to eat you, or at the very least, main you. What else is there to say about a time when the furthest place most people travelled was the next village, and yet their maps were crawling with creatures that made Lord of the Rings look like a nature documentary?

However, this wasn’t just idle fear; it was systematic, intellectual, and even theological. Back in the 13th century, readers weren’t exactly spoiled for choice when it came to maps. Unlike us modern people with our GPS and Google Maps, medieval readers had nothing more than the trusty old mappa mundi to guide them. These were, to be honest, more a theological doodle than a practical map. Forget about figuring out actual distances or locations; back then, you were navigating based on a moral compass, not a magnetic one.[1]

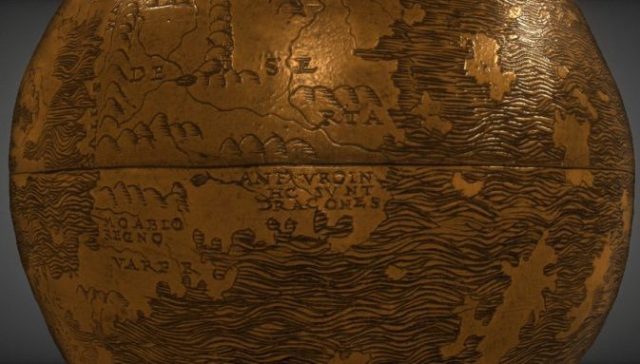

But when your only map is a giant religious allegory where Jerusalem sits comfortably at the centre and the rest of the world slides off into a chaos of monsters and mayhem, you can hardly be blamed for letting your imagination run wild. What else would you expect to find in the blank spaces beyond your reach? In a world where “Here be dragons” wasn’t just a handy label but a genuine warning, the unknown edges of the earth became a dumping ground for everything that terrified the medieval mind. No evidence? No problem. As far as medieval logic was concerned, if you couldn’t see it, it might as well be filled with dragons.[2]

“hic sunt dracones“ (here be dragons), Hunt-Lenox-Globe, copper, c. 1508, New York Public Library.

As historian Piero Camporesi notes, “People’s fears were exorcised by dumping them on those who inhabited the edges of the known world, who were lesser in some sense; whether troglodytes or pygmies (…) the outskirts are felt to be infected zones, where all kinds of monstrosities are possible”.[3] Thus, the margins of medieval maps became the breeding grounds for the grotesque and the alien, representing both geographical and spiritual distance from the known, Christian world. Because when you can’t prove what’s out there, why not make it at least very horrifying?

These terrifying fringes weren’t just some random artistic flourishes. No. This was the serious business of cartography. The further you got from Jerusalem, the centre of the world, the more deformed and alien things became. The edges of the map weren’t just where monsters lived; they were where the limits of representation stretched thin. Here, on the periphery of divine creation, monsters thrived. Whether Cynocephali (dog-headed men), Blemmyes (headless beings with eyes in their chests), or troglodytes, the monstrous races depicted in manuscripts and maps were not purely the product of fantasy. Many medieval illuminators believed they were faithfully representing creatures that, although bizarre, were part of God’s plan. Just not part of their immediate world.[4] It’s as if the more you veered from Christian salvation, the more you became a creature out of a bestiary manual.

Medieval Maps as Spiritual Roadmaps

Medieval maps were far more than colourful pre-Google-Maps marvels. If you think they were just primitive attempts at geographic accuracy, you’re missing the point. These maps weren’t trying (and failing) to get you from Point A to Point B. They were constructing entire worlds on parchment, infused with spiritual, cosmological, and sometimes also political agendas. As Michael Gaudio puts it, once a map is created, “the page becomes a landscape with its own spatial politics,” where a clear hierarchy of meaning is established; nature at the bottom, God’s word at the top.[5]

These maps weren’t exactly trying to be the medieval version of travel guidebooks. Think of them less as navigational aids and more as grand theological statements, organising space according to divine will rather than geography. Evelyn Edson wisely reminds us that “maps are not natural, self-evident statements of geographical fact.” Instead, the medieval mapmaker’s hand was guided by the mindset of his time, his social prejudices, and his religious concerns.[6] It’s not like they failed to measure the distance between London to Rome correctly. They just didn’t care. What they did care about was making sure you knew that Jerusalem was the centre of the universe, thank you very much.

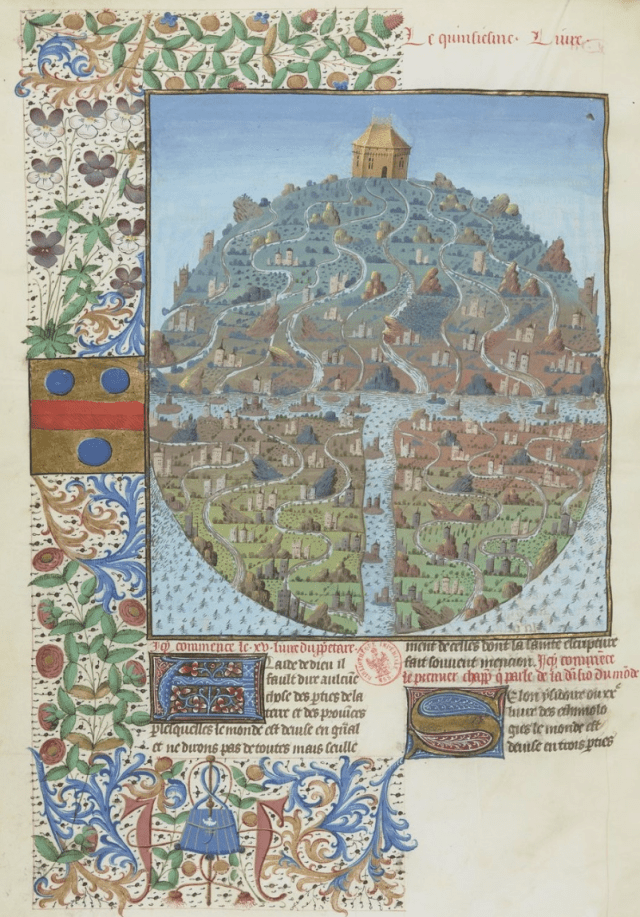

The simplest among medieval maps were the T-O maps, dividing the known world into three parts: Asia, Europe, and Africa, with Asia taking up the lion’s share. As for the T-divider, it wasn’t just an innocent divider of continents. Christians of the time, who could barely look at two crossed sticks without seeing a crucifix, decided that the T was a perfect stand-in for the cross of Christ. Suddenly, this simple map had become a visual reminder of salvation, conveniently laid over the entirety of human geography.

T-O-map (orbis tripartitus), illumination by Evrard d’Espinque for Jean Borbechon’s French translation of Bartholomaeus Anglicus‘ Liber de Proprietatibus Rerum of 1235, c.1480.

But if you were feeling adventurous, you’d opt for a mappa mundi with a little more flair. Enter the Ebstorf Mappa Mundi, where the earth was literally imposed onto the body of Christ. His head, hands, and feet marked the edges of the world; a handy visual reminder that if you sailed too far, you’d end up floating out of the divine frame. Not exactly a subtle message, but it certainly got the point across: stick to the centre, stay holy, and avoid the monsters.

Ebstorf Mappa Mundi, c. 1234-1240 (destroyed in 1943).

These grander maps, which include the Hereford Mappa Mundi, weren’t content with just showing places. They needed to give you a taste of what was out there: The unfamiliar, the exotic, and, of course, the monstrous. Marina Munkler points out that these maps were basically monster directories, with the borders packed with all manner of strange beings just waiting to horrify anyone brave, or foolish, enough to venture that far.[7] Because nothing says “cultural warning” like a line of headless men and dog-headed warriors standing between you and the great unknown.

John Friedman gets it: these maps are “an expression of contemporary cosmology and theology,” not useful objects for anyone planning a medieval road trip. Think of them as the worldviews of the time, neatly packaged on vellum and laid out for your contemplation, complete with moral lessons in the margins. They were grand statements about the order of the universe, with just a dash of monster-filled spectacle to keep things interesting.[8]

And if you’re wondering why the monsters all got stuck at the edges, well, that’s where they belonged. The further you got from the centre, the more you entered “infected zones,” where all kinds of monstrosities roamed free. The closer to the holy centre, the safer and more “civilized” you were.[9] The real magic of these maps wasn’t in their ability to represent the physical world but to impose meaning on it. They didn’t just show the way; they told you how to think about the world, how to feel about the unknown, and where you definitely shouldn’t go. These distortions weren’t accidents, they were statements. After all, maps don’t just represent reality. They create it.[10]

The Monks Who Never Left Home but Mapped the World

If you think medieval monks spent all their time praying and making honey mead, think again. Many of them were also busy creating some of the most elaborate, mind-boggling maps of the world – without ever leaving their cloisters! Yes, the same monks who took vows of stabilitas loci (meaning they vowed to stay put, not exactly the world’s best travel bloggers) were busy drawing entire worlds they had never seen. [11]

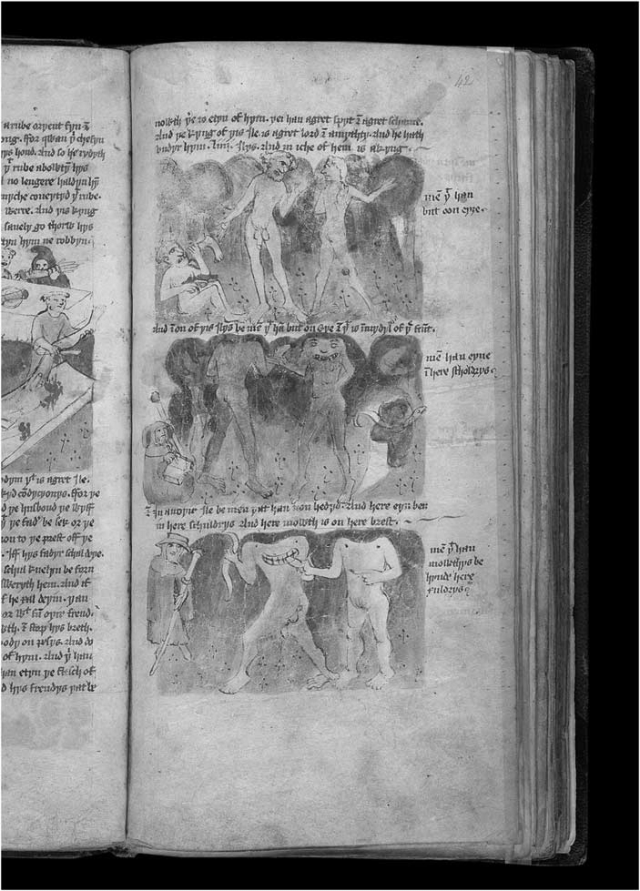

Let’s take Sir John Mandeville, for example. However, there’s some doubt that he even existed. Mandeville’s Travels spins some of the most spectacular yarns about distant lands and was one of the most popular travel accounts in the late Middle Ages, despite the inconvenient truth that he might’ve actually travelled to any of the places he describes. “There are many different kinds of people in these islands,” he writes, likely leaning back in his chair, entirely satisfied with his creative prowess. In one part, he tells us, there are giants with a single eye in the middle of their foreheads. Cyclops-like. “In another part, there are ugly folk without heads, who have eyes in each shoulder; their mouths are round, like a horseshoe, in the middle of their chest.” In another, there are people who don’t even bother with heads, instead putting their eyes on their shoulders and their mouths somewhere in the middle of their chest (a design flaw, surely!).[12]

Of course, we laugh now, but Mandeville wasn’t just making stuff up for the sake of it. He was drawing on a long tradition of medieval travel literature, combining a dash of classical sources with a heavy helping of creative license. The monks who lovingly illuminated these manuscripts in the cloister weren’t trying to give you a handy guide to your next vacation. Their maps weren’t supposed to be accurate – they were supposed to be meaningful. They used monsters, marvels, and far-off places as metaphors for everything from spiritual danger to moral lessons. The British Library holds a manuscript (Harley 3954, f. 42r) showing one of these delightful creatures in glorious medieval detail.

Cyclopes, Epiphagi and Blemmyes, Harley 3954, f. 42r, England 1400-1450, British Library, London.

The monks didn’t just invent monsters because they were bored; they were building entire worlds where the boundaries between known and unknown. It was a creative tour-de-force. Monks were masters of what you could call peregrinatio in stabilitate – a pilgrimage of the imagination.[13] Why walk all the way to China when you can sit in your abbey, stare at a map, and dream up horrors? It’s like armchair travelling, medieval-style, with a side of theological symbolism. The monsters weren’t just weird for the sake of it; they served as metaphors for spiritual and moral dangers lurking at the edges of Christian civilization.[14]

For example, consider the Le Livre des Merveilles du Monde, a French manuscript that blends fact and fiction with shameless bravado. The illustrations show strange creatures, from unicorns (most likely rhinoceroses that had a serious PR issue) to people with faces on their chests. The world beyond Europe became a stage for moral tales, reminding viewers that everything out there was exotic, dangerous, and just a little bit monstrous.

Monsters from the Land of Merkites described by Marco Polo, Le Livre des Merveilles du Monde, c.1410-1412.

Why Monsters? Why the Edges?

So why did Europe shove all its nightmares to the edges of the world? Medieval Europe’s understanding of the world was firmly rooted in its own supremacy. The centre of the world? Jerusalem, of course. The further you drifted from the Holy Land, the further you got from God’s grace. And if you sailed far enough, you’d eventually run into a host of creatures that strayed even further – morally, spiritually, and often physically – from the Christian ideal. It’s easy to imagine a monk, quill in hand, filling in the blank spaces on his map with monsters, nodding sagely at the thought of these unfortunate souls who had strayed from the path of righteousness (and proper anatomy).

But it wasn’t just about scaring people into staying home. There was an undeniable attraction to these monsters. Hegel, that dour German philosopher, suggested that Christian art was obsessed with pain and suffering – think of poor Jesus Christ on the cross – and, sure, that explains some of the physical deformities medieval artists loved to depict.[15] But monsters weren’t just about suffering; they were about the sheer wonder of it all. Medieval culture had a genuine fascination with the marvellous, the strange, the exotic. Why look for bland reality when you could imagine a world filled with unicorns and men with testicles so large they could be used as stools? (Yes, that’s a thing. Look it up.[16])

Let’s not forget the Greeks. Long before medieval Europe, the Hellenistic age had made a sport of contact with distant lands. Tales from the Romance of Alexander and Pliny the Elder’s Natural History were chock-full of fabulous beasts and races.[17] These were the stories that shaped medieval bestiaries, giving our European mapmakers the license to populate the fringes with creatures more exotic than anything reality could ever offer.

Monsters as the “Other”

Of course, monsters were more than just amusements. They were the ultimate form of “Othering” – a way for Europe to define itself by what it wasn’t. These headless, dog-headed, or giant one-eyed creatures represented everything foreign and terrifying. They were a convenient shorthand for all the cultural and religious fears of the time. The Cynocephali, for instance, those delightful men with dog heads, were often thought to live in India or Africa. Their existence signified the dangers of heresy, the “heathen” world, or simply the unknown. In short, if you weren’t Christian, you were probably a monster.

It wasn’t just individuals who got this monstrous treatment, though. Entire lands were painted as dangerous and untameable; places where the “civilized” rules didn’t apply. Enter Prester John who was the ultimate medieval fantasy: a Christian king ruling a vast, exotic empire at the edges of the world, surrounded by giants, horned men, and unicorns. His kingdom, mentioned in letters circulated around 1160, was more myth than reality, but it gave medieval Europeans hope that beyond the monstrous lands, a bastion of Christian virtue ready to help the fight against Islam.[18] Never mind that nobody ever found Prester John, or that he probably never existed. The idea was too good to let go of.

Fast forward to today, and you’ve got Edward Said pointing out how the West has long been obsessed with painting the East as “the Other.” Said’s work on Orientalism highlights how Western scholars, in their quest to define themselves, end up exoticising and belittling the cultures they study; making them seem weak, strange, and conveniently ready to be conquered.[19]

Marco Polo wasn’t above this game either. Polo didn’t just observe; he crafted a narrative of total “otherness” between Christianity and non-Christianity, a textbook move in colonial discourse. How did he do it? By focusing on the so-called “disorders” of the East, monsters like unicorns and dog-headed men, along with their supposedly strange diets ( say cannibalism) and, of course, the obligatory mention of bizarre sexual customs.[20] Polo wasn’t just describing a place; he was subtly mapping out a world ready for domination.[21]

Marco Polo and the Unicorns That Weren’t

If we return to our favourite medieval journalist, Marco Polo, who actually did travel to the edges of the known world, but even he couldn’t escape the grip of Europe’s monstrous imagination. While in Java, Polo reported seeing unicorns. Except, as he dutifully clarified, they were not quite the dainty, virginal unicorns his readers expected. No, instead, they were big, ugly, and unpleasant to look at. Rhinoceroses, in fact.

Polo, ever the honest journalist, admitted that unicorns “do not let themselves be caught by a maiden” and were more likely to crush her with their knees than politely submit.[22] These unicorns didn’t exactly fit the medieval fantasy, and Polo was just the unfortunate guy who had to deliver the bad news. He wasn’t lying; he was simply caught between the wonder of the unfamiliar and the weight of centuries of European expectation. The world was full of strange things, and sometimes it was easier to call a rhino a unicorn than to rewrite the entire medieval bestiary.

Why Monsters Will Always Be at the Edges

In the end, monsters weren’t just a medieval oddity. They reflected a deep psychological need to define the world in moral and spiritual terms. By placing monstrosities at the edges of the map, medieval Europe could both fear and marvel at the unknown, all while reassuring itself that the centre was safe and civilised. Monsters served as a way to push the dangers and uncertainties of life out to the margins, where they could be contained and controlled.

After all, monsters served a purpose. They protect us from the unknown, giving shape to our fears, while offering just enough wonder to make us curious. The medieval imagination turned the edges of the world into a stage for humanity’s deepest anxieties – and its most fantastic dreams.[23] Because let’s face it, why focus on the mundane realities of distant lands when you could imagine a world filled with unicorns, dog-headed men, and giant one-legged monsters who used their massive feet as parasols? It’s a far better story.

Further reading

Camille, Michael, Image of the Edge. The Margins of Medieval Art. London: Reaktion Books, 1992.

Delano-Smith, Catherine, and Roger J. P. Kain, English Maps: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999.

Edson, Evelyn, Mapping Time and Space: How Medieval Mapmakers Viewed Their World. London: The British Library, 1997.

Friedman, John Block, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Gaudio, Michael, “Matthew Paris and the Cartography of the Margins,” in: Gesta, 39:1 (2000), 50-57.

Harley, J.B. and David Woodward, hrsg., The History of Cartography, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich., Philosophie der Kunst oder Ästhetik. Nach Hegel. Im Sommer 1826. Mitschrift Friedrich Carl Hermann Victor von Kehler, hrsg. v. Annemarie Gethmann-Siefert and Bernadette Collenberg-Plotnikov. München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2004.

Manzul, The Ethics of Travel: From Marco Polo to Kafka. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996.

Larner, John, Marco Polo and the Discovery of the World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

Mandeville, John, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. London: Penguin Classics, 2005.

Mittman, Asa Simon, “Are the ‘monstrous races’ races?”, in: postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies 6:1 (2015): 36-51.

Mittman, Asa Simon, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Mittman, Asa Simon (Hrsg.), Primary Sources on Monsters. Cambridge: Cambridge Unversity Press, 2021.

Munkler, Marina, “Experiencing Strangeness: Monstrous Peoples on the Edge of the Earth as Depicted on Medieval Mappae Mundi.” in: The Medieval History Journal, 5, 2 (2002): 195–222.

Polo, Marco, Die Beschreibung der Welt, transl. August Bürk, Erdmann Verlag, 2021.

Said, Edward W., Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Wood, Denis, The Power of Maps. London: Guilford Press, 1992.

Van Duzer, Chet, Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps. London: British Library Publishing, 2013.

[1] John Larner, Marco Polo and the Discovery of the World, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 91.

[2] Chet Van Duzer, Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps (London: British Library Publishing, 2013), 61-63.

[3] Piero Camporesi, embedded quotation is from Michael Camille, Image of the Edge. The Margins of Medieval Art, (London: Reaktion Books, 1992), 14.

[4] Asa Simon Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England, (New York: Routledge, 2006), 35.

[5] Michael Gaudio, “Matthew Paris and the Cartography of the Margins,” in: Gesta, 39:1 (2000): 50-57, 52.

[6] Evelyn Edson, Mapping Time and Space: How Medieval Mapmakers Viewed Their World (London: The British Library, 1997), 16.

[7] Marina Munkler, “Experiencing Strangeness: Monstrous Peoples on the Edge of the Earth as Depicted on Medieval Mappae Mundi.” in: The Medieval History Journal, 5, 2 (2002): 195–222, 195.

[8] Friedman (1981), 101-105.

[9] Gaudio (2000), 52.

[10] Denis Wood, The Power of Maps, (London: Guilford Press, 1992), 26.

[11] Asa Simon Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England, (New York: Routledge, 2006), 31.

[12] John Mandeville, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, (London: Penguin Classics, 2005), 137.

[13] Asa Simon Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England, (New York: Routledge, 2006), 31.

[14] Catherine Delano-Smith, and Roger J. P. Kain, English Maps: A History, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 18-22.

[15] Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Philosophie der Kunst oder Ästhetik. Nach Hegel. Im Sommer 1826. Mitschrift Friedrich Carl Hermann Victor von Kehler, hrsg. v. Annemarie Gethmann-Siefert and Bernadette Collenberg-Plotnikov, (München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2004), 136.

[16] Asa Simon Mittman, and Peter J. Dendle, eds. The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2012, 49-55. Also in: Friedman, John Block. The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981, 101-105.

[17] Asa Simon Mittman (Hrsg.), Primary Sources on Monsters, (Cambridge: Cambridge Unversity Press, 2021), 43-48.

[18] Friedman (1981), 50-53.

[19] Edward Said, Orientalism, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978).

[20] Syed Manzul Islam, The Ethics of Travel: From Marco Polo to Kafka (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), 27-30.

[21] Larner (1999), 97-98.

[22] Marco Polo, Die Beschreibung der Welt, übersetzt von August Bürk. (Erdmann Verlag, 2021), 227.

[23] Michael Camille, Image of the Edge. The Margins of Medieval Art, (London: Reaktion Books, 1992), 14.